1968

RAEME in South Vietnam

BY BRIGADIER J. C. DEAN, O.B.E., F.I.E.Aust.

Brigadier John Dean was the Corps Director from 1969 to 1975. Prior to that appointment he was the Deputy Director.

As DEME/DGEME he lead during two testing periods for the Corps, one being The Vietnam Conflict and the other, the major reorganization of the Army into Functional Commands including the transfer of all RAEME personnel from the RAEME List to the Army List.

This article by him, written for a REME audience, was published in the REME Journal in 1971. Copyrights stand

Background

Left and Right polarised about Hanoi and Saigon respectively and a flood of refugees moved south to join the Republic of Vietnam. In the north, the communists formed the Democratic People's Republic of Vietnam and immediately began insurgent activities in the south aimed at the seizure of power in Saigon.

Australia watched these developments uneasily. We had recently learnt just how close we are to Asia and our forces had participated in the elimination of communist subversion in Malaya. It was logical that, when requested assistance by the Saigon government, Australia should join the Americans and allies in countering the new threat.

In July 1962 a group of 30 Australian officers and warrant officers took up duty as advisers with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), to form the nucleus of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam, our first contribution to what was hoped would be a low-key campaign. But this was not to be the shape of things.

In the face of Saigon's and the US and its allies' reactions, North Vietnam increased its pressure with further support for the southern Viet Cong and the covert commitment of northern army units. On 29th April 1965 the Australian Prime Minister announced that the 1st Bn Royal Australian Regiment and a logistic element would join ARVN and US forces in the field in South Vietnam; in July, the New Zealand government committed a field battery in support. In Australia, National Service for a selected number of 20 year olds enlisted for two years was introduced in mid 1965.

In March 1966, the ANZ contribution was increased to a two battalion task force and by 1968 this had been augmented by a third battalion, a tank squadron and sufficient logistics elements to maintain this powerful small force in the field. Royal Australian Navy and Air Force units have also played important parts in operations for several years.

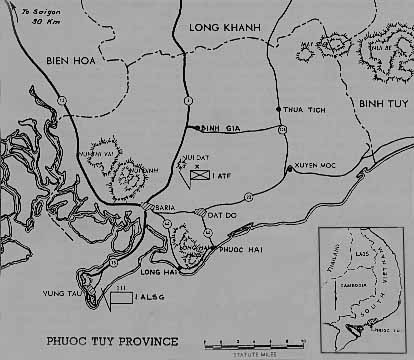

At the time the force was upgraded to two battalions, it was allotted Phuoc Tuy Province as its main operating area, with headquarters at Nui Dat and its logistic support units at Vung Tau.

The foregoing brief background is necessary to put the reader in a position to focus the progress of RAEME support for 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF) operations.

Considerations for RAEME

In outline, this kept step with the change in force strength : in detail, it involved hard bargaining to secure adequate manpower for the task, an elaborate personnel programme including a minor revolution in technical training to man it, and at the same time a heavy increase of workshop loading in Australia to augment it.

The three chief aspects which determine EME support for operations are

- the order of battle,

- the concept of operations, and,

- the equipment of the force.

Order of Battle

By 1968, 1ATF comprised three infantry battalions, an SAS squadron, a tank squadron, an APC squadron, a field regiment, a detachment of the divisional locating battery, a signal squadron, a field squadron, aviation, and supporting services, including EME.

The 1st Australian Logistic Support Group (1ALSG) incorporated a construction. squadron, a supply and transport company with supply, transport and air despatch elements, a field hospital, an advanced ordnance depot, a field workshop, and various minor units and attachments.

The force was, in fact, a microcosm of the Australian Army; it incorporated an infantry, company and a field battery of New Zealanders.

Concept of Operations

The concept of operations involved the establishment of the Task Force at Nui Dat, a central, accessible location within the province over which a continuous series of patrol activities were mounted. These activities generally were infantry operations to comb successive areas of the province mounted either from the main task force base or from suitably located fire support bases.

The procedure was to locate enemy areas using every means at hand, then rapidly insert infantry with armour and artillery support, thus forcing contact to destroy the enemy and his hold over the village and hamlet communities.

Additionally, much use was made of utility, medium and at times heavy helicopter lift of forces and their maintenance. 1ATF was thus a largely self-sufficient force requiring only daily maintenance to keep in operation.

Maintenance was provided from the port and MRT airhead area of Vung Tau, about 20 miles distant and accessible by road and air. There, a hard-scaled logistic base received maintenance from Australia or US sources and distributed stores forward. There were held the repair and maintenance pools of equipment which were so scaled that units could be kept at near full equipment entitlements at all times.

The Equipment of the Force

The main weapons of the force were

- the L1A1 and M16 (Armalite) rifles, the M60 machine gun, 81-mm mortar,

- M2A2 howitzer 105-mm and,

- until mid-71, Centurion Mk5.

- M113 type APCs and derivatives were used, including a 76-mm gun fire support vehicle.

- International 2½ and 5-ton trucks and dump trucks and 108-in Land-Rovers were the work vehicles.

- Radio was basically the AN/PRC 25 family including vehicular relatives of the AN/GRC 125 type; whilst Centurion was in theatre, the C42 family was in service.

- Engineer equipment of a wide variety was used ranging down from Caterpillar D8s armoured in theatre by RAEME to the Case Size 0 dozers used to develop fire support bases when on air landed operations.

- Cessna and Pilatus Porter fixed wing and Bell Sioux and Kiowa helicopters were Army operated.

- A wide range of generator sets was used

- the base areas being permanently supplied from Caterpillar powered 62.5 kVA,

- the main field sets being Volkswagen-engined 10 and 15 kVA and 350A welders, and

- a variety of small sets used at unit level for special purposes.

- And then the whole range of minor equipments-typewriters, compasses, chain saws, telephones-you name it, 1ATF or 1ALSG had at least one!

Repair and Recovery Support

In the Australian Army, RAEME responsibilities parallel those of REME in the UK service: during the Vietnam war, RAEME was the repair agency for all field force equipment except engineer equipment of a few types such as stone crushers and bitumen sprayers, and signal equipment on RA Signals charge; the two operating Corps carrying out up to field repair. Thus RAEME needs capacity at every level to repair almost any equipment which the Army may hold (RAEME responsibilities are being widened and this comment is now even more pertinent).

A comprehensive repair and recovery plan within which to deploy and operate resources is essential in any circumstances

After initial difficulties imposed by staff limitation of EME manpower at all levels, capacity was developed to permit appropriate deployments in support of any type of operation which the field command could contemplate, based on the well established principles of

- repair as far forward as practicable, and,

- flexible employment of all resources.

At the same time, because of the distance from the Australian home base and the infrequency of heavy lift shipping; a regular supply ship operating on a six weeks turnaround schedule

- depot stocks were built up to establish necessary repair and maintenance pools of critical equipments, and,

- the field workshop of lALSG undertook a share of repair of depot stock, to reduce evacuation to Australia.

Meanwhile back in Australia, planned base repair of evacuated equipment took its place in the general logistic plan for the Force.

Infantry Battalion EME Attachments

Australian infantry fight on foot using highly developed techniques of vigorous patrolling, cordon and search, ambush and any other means possible to bring insurgents into combat. Insertion into operations was frequently by helicopter in company lifts, by truck or APC, the latter being more frequently used in closer contact.

For this role, a battalion has thirty two Land-Rovers with trailers as integral transport for heavy weapons, ammunition and stores.

RAEME attached comprise a sergeant, corporal and craftsman armourers, a corporal and two craftsmen vehicle mechanics and a corporal radio mechanic; a utility shop truck and trailer carrying hand tools, portable pedestal drill, portable bench grinder, gas welding set and a 22kVA generator is available for them to move and work from.

Some battalions arrange for this RAEME group to work together, others locate them in lines with the unit Q, transport, and signals elements respectively; in the Nui Dat base, each battalion had its own preferences.

These men maintained, as well as the normal war equipment, seven additional heavier vehicles for domestic use, grass cutting machines, and various other useful items.

As each battalion was on continuous operations during its one year in theatre, work was always in hand, each rifle company's weapons receiving RAEME attention at regular intervals when it was in the base or whilst on occasional short breaks in the Vung Tau rest centre, where an armoury was set up for the purpose.

Work of unit armourers was supervised by the Task Force Armourer, a W02 Armament Artificer, whilst an independent check and advice upon unit maintenance was made by a RAEME Equipment Inspection Section controlled by Force Headquarters.

Battalions always arranged for each soldier to fire the weapon he was to take into action into an underground butt in the unit base, with armourer support immediately available. Tradesmen were taken or called forward by the battalion into a fire support base to deal with immediate repair tasks.

Light Aid Detachments

The tank and APC squadrons, the field regiment and Task Force Headquarters were each serviced by an appropriate LAD.

Armour and Cavalry Light Aid Detachments

It became normal for the tanks, generally operating in the infantry close support role, to have along an apparent excess of ARVs ... two per squadron ... as well as part of their LAD in a fitters' tracked carrier, the M113A1. The elderly Centurions proved rather unreliable, despite devoted attention.

The APCs were generally supported by a small section in a fitters' track, which also cared for the fire support vehicles; an Australian adaption of the M 113 carrier mounting the very effective Saladin 76-mm gun turret.

Artillery

The field regiment LAD deployed its battery sections into fire support bases as required. Because of the comparatively low rate of battle casualties, all LADs were encouraged to extend their scope of repair to match capacity: a situation which can be readily reverted to normal when repair pressure builds up for any reason.

When deployed, the LADs also showed remarkable adaptability in additional work, including assistance to US SP medium artillery, frequently in location.

Unit Workshops

Unit workshops were provided for field and construction squadrons, the light aircraft flight, and transport company. These were all heavily engaged in the unit repair of all equipment of their parent units and field repair of the specialist items.

Each is capable of deploying forward repair teams in support of its dependency, the engineer squadron workshops being equipped with fitters' tracked carriers for this purpose. Due to the nature of operations, it was normal for the main body of each shop to be hard at work in the base location, with a detachment out repairing equipment casualties at work sites.

Task Force Field Workshop

Prior to the addition of tanks to 1ATF, field repair support for all items other than those covered by unit workshops was provided by a field workshop in the logistic base at Vung Tau.

Because of the twenty miles separation of the task force base from this area, much time was lost in moving repairable equipment and the route was always threatened with enemy interdiction. At that time, the Staff was not keen to have a workshop detachment forward at Nui Dat, nor indeed, was the Force EME, because of the relative inefficiency which resulted when operations made a detachment essential.

With the lodgement of tanks in 1ATF, a field workshop was established in the task force base to

- provide second line support for them, and,

- obviate back-loading field repairs from the battalions and LADs to the Vung Tau base.

This workshop was provided with

- a solid tank shop and had the usual A and B vehicle sections;

- a general engineering shop with a high capacity for welding including light alloy work;

- communications, instrument and recovery sections. This last was equipped with an ARV, medium wreckers and tilt-bed trailers.

- The workshop had a high capacity Stores Section RAAOC under command.

In addition to its repair task as a major unit, the workshop was responsible for several hundred metres of the base perimeter, a defence task requiring the establishment of a strong point and employment of daily first and last light clearing patrols. The two unit fitters' vehicles with their .5 inch Brownings and radios were useful adjuncts to the defence, when in location.

To conform with the staff requirement for minimum manpower, when originally deployed this unit was designated as an armoured squadron workshop in direct support of only the tank squadron.

Although we had successful tank unit workshops in the Second World War and had tested the organization in some detail during exercises in Australia, it foundered under the operational stresses of Vietnam.

The rescue operation set up the larger, but nevertheless restricted, field workshop with the more sophisticated structure already described which then matched its new tasks.

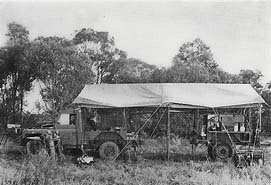

In the normal field unit manner, it was originally equipped on a mobile basis with a mixture of 2½ton and 1ton repair trucks. The tank workshop and ancillary shops were then built and much of the mobile equipment was withdrawn, the unit being left with a static shop with dismounted machines and a ¾ton based light-scaled facility for the forward repair role, usually carried out in the outlying fire support bases.

Logistic Support Group Field Workshop

With the establishment of a field workshop in 1ATF, the role of the ALSG field workshop changed to provide greater support for the Advanced Ordnance Depot, also in 1ALSG, whilst direct support to the domestic units of the Group continued. It became possible to extend theatre repair limits for many equipments and markedly reduce evacuation to the home base.

When deployed to the theatre, this workshop was completely mobile. Prefabricated steel workshop, stores and office buildings were sent from Australia for this as for the other logistics units, and a valuable permanent workshop was, by degrees and with a lot of self-help, established.

Vietnam Operational Factors

What characterized the operations in South Vietnam, to make them distinctive from an electrical and mechanical engineering viewpoint? The same factors, of course, which bore upon the operational elements of the force to cause new techniques to be adopted in countering communist revolutionary warfare

- the nature of the enemy threat related to the country and

- the people amongst and for whom the continuous battle is fought.

Phuoc Tuy Province is a fairly flat tract about 50 km square, from which rise a few rocky outcrops to heights of 100 to 500 metres. Several of these, like Nui Dat itself, are conical, about a kilometre across. Others are several kilometres in extent and, to the northwest of the Province, descend into undulating country. The relatively flat areas are covered in rain forest or scrub or have been cleared for rubber plantations or paddy.

Population centres on the plains or coast vary from large villages ... Baria, the Provincial centre, has a population of about 15,000 ... to hamlets of a few hundred farmers or fishermen. These are connected by narrow roads on which the heaviest traffic had been the 3-ton trucks of the rubber plantations. From these roads, spur tracks run to the farms and plantations.

Before the entry of 1ATF, the province was not controlled by the government, the Viet Cong using it as a supply and rest area. The enemy knows the province well and has family connexions in many of the villages. The destruction of the VC infrastructure and subsequent denial of spheres of influence were the tasks of 1ATF. Hostile reactions came, on a decreasing scale, from every area entered until government influence was established by combined military and civic action. The VC strength was whittled away and his remnants took to strongholds in the hills or rain forest. These strongholds were the product of thirty years warfare and were too numerous to destroy permanently. From them the enemy sallied forth to set ambushes or for re-supply and tax collection purposes.

Hence the EME action was to cope with equipment casualties due to enemy ambush, to breakdown or ditching due to the poor going, or to the heavy wear and tear on equipment in tough, tropical conditions. In all units RAEME soldiers took their turn in patrols, particularly the daily clearing patrols outside the base perimeters.

Ambushes were usually initiated by mining a road, track or approach, followed by attacks by fire of small arms or rocket propelled grenades on troops and vehicles in the ambush area. Mines used were of the infinite variety of the guerilla and their effects equally variable. Recovery, forward repair or back-loading of casualties to base were the RAEME requirements, equipment never being left in the field. Some mine damage and most strikes were repairable in theatre, heavier casualties being brought back to Australia.

To cope operationally with these casualties, it was early found that the personal weapons of recovery crews were inadequate for protection. APC escorts were required and the recovery crews issued with GPMGs; the .5-inch Browning mounted on the fitters' track proved its value. Careful reconnaissance of routes in to casualties, and out again before recovery, was mandatory-rapidly placed enemy mines were to be expected.

Bad going is always an enemy of equipment. Poor roads and tracks, paddy bunds, bamboo thickets, tree stumps and small trees were hard on vehicles, whether tracked or wheeled; the attendant dust in the dry season and mud of the wet were both sources of attrition to any weapons, vehicles or other exposed material. At the same time, heavy construction efforts were made to improve roads: tippers and plant logged phenomenal hours.

A peculiar problem arose with Centurion 'scrub-bashing' in support of infantry, due to the build-up of scrub rubbish in and around the tracks leading to removal of skirting plates and minor shortening of the splash guards. (Originally done in theatre, this was later incorporated as part of the base repair process.)

Further, due to the low classification of roads and bridges, tanks and heavy plant covered many more track miles than would be 'normal' to their missions. For all these reasons, automotive and general engineering work, especially welding, were very heavy.

A new and originally unplanned role for RAEME was provision of technical assistance in the civic action tasks which the force undertook. In every town, village and hamlet, work to improve the life pattern of the population was a feature

- wells were bored,

- school-rooms built and equipped

- playgrounds made for the children,

- hospital facilities developed and built,

- carts and bicycles repaired.

Most of this was done by Sapper teams but the special skills of EME were continuously in use and, throughout the Province, the red, yellow and blue of the Corps still appears on many fabricated structures particularly school ground equipment; welders and welding equipment were the most exercised, but many individuals were able to make special contributions.

Probably the most singular EME characteristic developed in this campaign was the settling of field units into static accommodation, with the need to retain only a fraction of the mobility which would be their normal attribute. This was an anachronistic situation: combat arms of the highest mobility, flexibly employing the latest surface and aerial means of deployment, carried out much unit maintenance and received direct support from efficiently organized static bases. Future thinking in the Australian Army will be coloured by this: we in RAEME must remain aware of the other, more mobile, demands which will probably confront us in the future.

Brief mention has been made of the introduction of National Service for the Australian Army. RAEME finds about a quarter of its strength from this source: a number of junior officers, many of them qualified engineers, and the remainder mostly rank and file. In Australian Force Vietnam, a somewhat higher percentage of RAEME members were national servicemen, mostly journeymen tradesmen whose task in the Army was to fill this role. There is no distinction between regular and national servicemen, all fitting into the team and playing their respective parts with vigour and good sense; the skills brought by these men from the civil sector are readily adapted to their Army work, some of course, in cases such as A vehicle mechanics or gun fitters, requiring equipment training on short courses at the RAEME Training Centre.

Last Words

He would be arrogant who claimed that there is no scope for improvement of the EME approach to equipment maintenance. But the record of support, at all levels within the Force and from the mainland base, given to a difficult operation by the Corps, speaks strongly for the wide-ranging and penetrating engineering organization which it embraces.